OBJET! PT 1: COURTESANS & OBJET| INDIA & FRANCE

In the glittering salons of 19th century Paris, an onyx bathtub stood as testament to the extraordinary paradox of courtesanship and power. This extravagant piece, commissioned by La Païva for her Champs-Élysées mansion, where yellow onyx staircases and baroque frescoes competed for attention, was more than mere opulence – it was a statement.

Images from The Hotel de la Paiva.

It’s women’s month over there at DECADENT MATERIAL, and the topic of the period is “COURTESANS: COLLECTORS & THE COLLECTED” and as its sister blog, we’re following suit over here. Throughout history and across diverse cultures, courtesans—known variously as Tayu, hetaeras, tawaifs, and high-ranking entertainers—have occupied a unique cultural position at the intersection of art, intimacy, and commerce. These women exchanged artistic accomplishments, intellectual conversation, and sexual favors with elite male patrons, creating sophisticated spaces of cultural production that often existed outside traditional societal frameworks.

Studying courtesans offers a profound lens into the complex relationships between beauty, social capital, and economic survival. Throughout history, courtesans have embodied a unique social position that simultaneously challenges and reinforces systems of power, gender, and economic exchange. They represent a nuanced form of agency within societies that often restricted women’s economic and social mobility.

Tawaifs from India, Oiran from Japan & A French royal mistress.

The first OBJET! blog post of 2025 examines the material culture of courtesanship, focusing on how luxury objects functioned not merely as possessions but as powerful instruments of self-definition, economic independence, and cultural influence. Of particular significance is how these objects served as retirement investments—portable assets that could provide financial security when age or changing circumstances ended their professional careers. So, for Part 1 we’re focusing on France & India.

HIERARCHIES OF SEX WORK

&

THE ECONOMICS OF LUXURY

Before examining specific cultural contexts, it is essential to understand that courtesans represented only the elite tier within broader hierarchies of sex work. Across cultures and time periods, clear distinctions existed between common prostitutes and high-status courtesans, with multiple gradations between these extremes. A woman's position within this hierarchy determined her access to luxury goods, her ability to accumulate wealth, and her opportunities for financial security later in life.

INDIA

The term "tawaif" derives from Urdu-Persian, literally meaning a wandering tribe or community, referencing the initially itinerant nature of early courtesans who established themselves wherever army camps or cantonments existed. To distinguish between common prostitutes and tawaifs, scholars cite Martha Feldman and Bonnie Gordon's definition from "The Courtesan's Arts: Cross-Cultural Perspectives," where courtesans are described as women who "engage in relatively exclusive exchanges of artistic graces, elevated conversation, and sexual favors with male patrons."

Gauhar Jaan famed Twain

In North India, particularly in Lucknow, a well-defined hierarchy existed within the world of female performers and sex workers. The tawaif ecosystem was as complex and structured as the society it emerged from. At the top of this hierarchy was the chaudharayan—a chief courtesan who, having accumulated significant wealth and fame, would retire to manage the establishment.

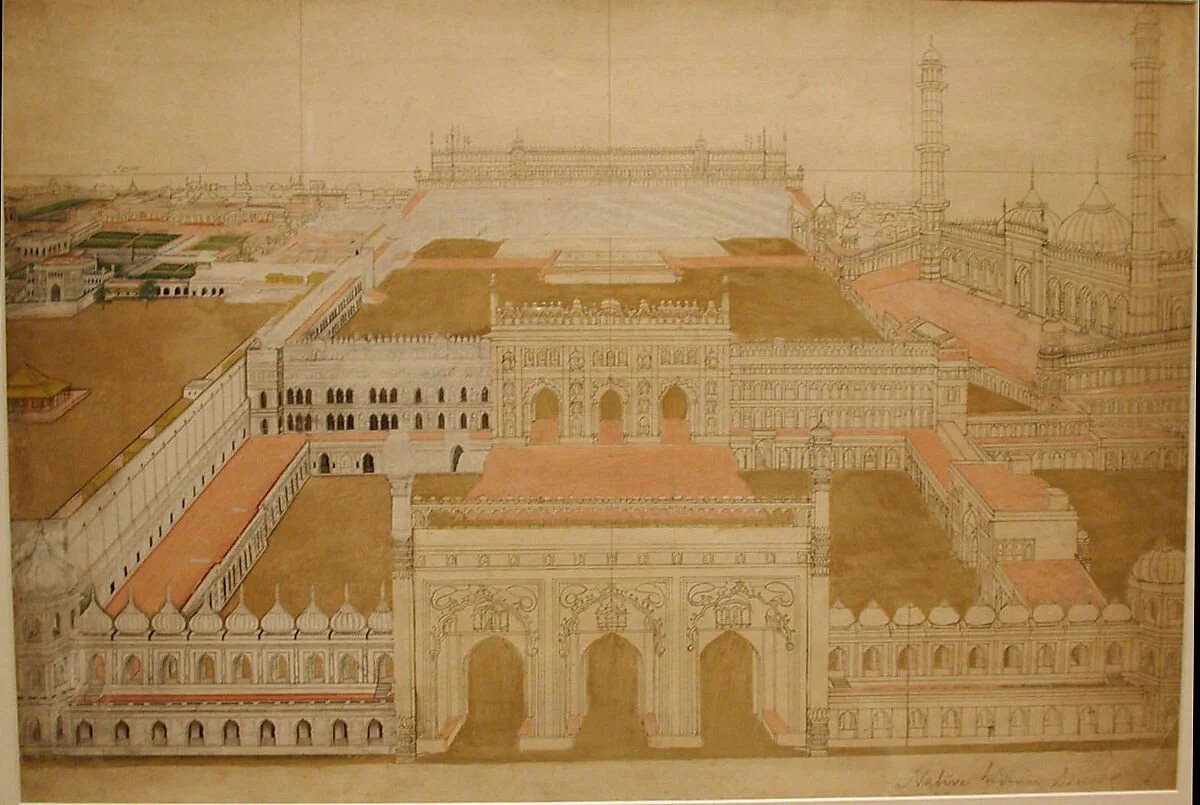

Lucknow, India

At the bottom were the “common prostitutes” in red-light districts; above them were the Kanchanis from Delhi and Punjab who worked in bazaars; the lime sellers (chune waliyan) occupied a middle position, with some achieving fame through exceptional singing talents. The Nagrani from Gujarat represented another distinct category.

At the apex of this hierarchy stood the tawaifs, who represented the height of cultural refinement. As Pran Nevile affirms in "The Nautch Girls of the Raj" (2009), they were "highly sophisticated courtesans brought up in accordance with age-old custom and tradition." Over time, they served as the most refined and coveted cultural disseminators of North Indian arts.

Within the tawaif category itself, further distinctions existed. The most elite were the khandani tawaifs (family-based courtesans) who inherited their position through matrilineal traditions, followed by the nachne-gane wali tawaifs (performers of dance and song), and finally the randi tawaifs who primarily offered sexual services. A tawaif's position within this hierarchy determined her access to wealthy patrons, her ability to accumulate valuable possessions, and her prospects for long-term financial security.

As historian Veena Talwar Oldenberg poignantly reveals, the story of tawaifs is a tale of systematic erasure and misrepresentation. Known by various names across India—tawaifs in the North, devadasis in the South, baijis in Bengal, and naikins in Goa—these professional singers and dancers were brutally reduced to “nautch girls” during British colonial rule. Their rich cultural legacy was deliberately scrubbed from historical memory, their profound contributions to classical arts marginalized and forgotten.

In reality, they were cultural luminaries who stood at the very epicenter of artistic and social sophistication. During their golden era, particularly under Mughal rule, they were not just performers but powerful cultural architects, economic powerhouses, and social strategists of unparalleled brilliance.

UMRAO JAAN

Umrao Jaan emerges as a critical text in understanding tawaif representation although it has been argued that it is not completely accurate in the sense that it shows the courtesan culture as something one is forced into, the movie is otherwise a Hindi cinema classic,.Originally a novel by Mirza Hadi Ruswa (1899) and then Adapted into multiple film versions (notably 1981 and 2006). The representations of tawaifs in Indian media, particularly through the narrative of Umrao Jaan, reveals the intricate negotiations of beauty, art, and social capital.

Umrao Jaan 1981 and 2006

Umrao Jaan reveals:

• Beauty as a form of economic and cultural capital

• Artistic skill as a means of social negotiation

• The intersectionality of gender, art, and economic survival

• Resistance within systems of social constraint

MATERIAL CULTURE:THE TAWAIFS & THE KOTHA

Imagine mansions filled with the most exquisite treasures. The 'kothas,' the residences of the Tawaifs, were not today's brothels but rather sanctuaries of art and etiquette. Mughal royalty and nobles often sent their offspring to these 'kothas' to learn manners, music, and dance. These could rightfully be called the 'etiquette institutions' of their era.

Still from Umrao Jaan 1981

Their collections and relationships with objects are stuff of legend. Beyond their virtuostic use of musical instruments—particularly the sarangi and tabla—tawaifs accumulated significant collections of manuscripts, poetry anthologies, and musical compositions that preserved and developed North Indian classical traditions. Many established tawaifs maintained extensive libraries of Persian and Urdu poetry, reflecting their roles as cultural custodians during periods of political transformation.

Tawaif playing the Sarangi

In her research on Lucknow's courtesan culture, Veena Talwar Oldenburg documents how tawaifs' collections of musical compositions and technical treatises functioned as repositories of cultural knowledge, particularly as traditional patronage systems declined under colonial rule.

Mughal Era Jewels: Belt Brooch by Cartier

Platinum, set with emeralds, sapphires, and diamonds

They were passionate connoisseurs and patrons of jewellery and their collections were nothing short of extraordinary – diamonds, emeralds, rubies, and pearls crafted into elaborate pieces that told stories of wealth, taste, and cultural sophistication. From intricate maang tikkas that adorned their foreheads to delicate hath phools that transformed their hands into works of art, every piece was a carefully curated statement. The chhapkā and jhūmar were not just accessories, but declarations of their unique aesthetic sensibility.

Mughal Era Jewels

Their living spaces were a testament to their immense wealth and highly cultured taste. Literary traditions like the aforementioned Umrao Jaan Ada, aided in immortalizing their elegance. The protagonist of Mirza Hadi Ruswa's novel, became a symbol of refined beauty – her rich silks, intricately embroidered costumes, and exquisite jewellery painting a portrait of a woman who was as much an artist as she was a performer.

Still from Umrao Jaan 2006

Tax records and seized inventories revealed that many kothas contained:

• Gold and silver ornaments encrusted with precious stones

Mughal Era Jewels: A Belle Époque diamond Jigha, the turban ornament set with old, baguette and pear-shaped diamonds, white gold, fitted with plume holder on the reverse, lower portion detachable, 5¾ in., 1907 and remodeled circa 1935. Estimate: $1,200,000-2,200,000. Offered in Maharajas & Mughal Magnificence on 19 June 2019 at Christie’s in New York

• Embroidered cashmere wool and brocade shawls worth fortunes

• Bejeweled caps and shoes that sparkled with every step

Still from Umrao Jann 2006

• Silver, gold, jade, and amber-handled accessories

• Elaborate silver cutlery and jade goblets that reflected their status

Mughal Era Jewels:Nephrite jade Pen Box and Utensils

17th century (made). set with rubies, emeralds and diamonds

Similarly, Vasantasena from the Sanskrit play Mrichchakatikam became legendary for her opulence, her jewels so abundant that she could fill a child's clay cart with her treasures.

Still from the movie Vasantasena, 1956

The material environment of the kotha (salon) was carefully arranged to display both wealth and cultural refinement. Tawaifs invested significantly in architectural spaces that facilitated their performances, with specialized areas for music, poetry recitation, and private entertainment. Their collections of textiles—particularly fine Banarasi and Lucknowi chikan embroidery—were renowned, with many tawaifs supporting local artisans through their patronage.

THE ART OF LUXURY EXTRACTION

The tawaifs elevated the art of luxury to an unprecedented level. Their training went beyond performance; it was a complex strategy of financial and social manipulation:

• They mastered nakhrah, an intricate art of persuasion and theatrical negotiation

• Each interaction was a carefully choreographed performance designed to extract maximum financial benefit

• They could coax extraordinary sums from patrons through subtle, refined techniques

• Their goal was always clear: amass wealth rapidly and invest in income-producing properties

Edwin Lord Weeks

The Dance

PATRON RELATIONSHIPS: A STRATEGIC ALLIANCE

A typical relationship with a patron was a meticulously negotiated arrangement. A wealthy courtier, often the king himself, would bid for a tawaif’s exclusive companionship. This came with specific privileges and obligations:

• Regular monetary and jewelry contributions

• Exclusive social and intimate privileges

• Access to elite soirées and cultural gatherings

Valentine Cameron Prinsep, R.A. (1838-1904)

Martaba, a Kashmiree Nautch girl

Perhaps their most enduring fashion contribution is the 'Anarkali' – a gown-like dress with a full skirt. Named after the famous courtesan Anarkali, this garment was meticulously designed with dancers in mind. Its silhouette was perfect for graceful whirls, allowing performers to create mesmerizing movements during poetry & performances.

As Oldenberg documents, the most prestigious tawaifs, known as deredartawaifs, claimed direct lineage from royal Mughal courts. They were not peripheral figures but integral members of royal retinues. To be associated with a tawaif was the ultimate symbol of status, wealth, sophistication, and cultural refinement. No one viewed them as objects of pity or disrepute—they were respected cultural icons.

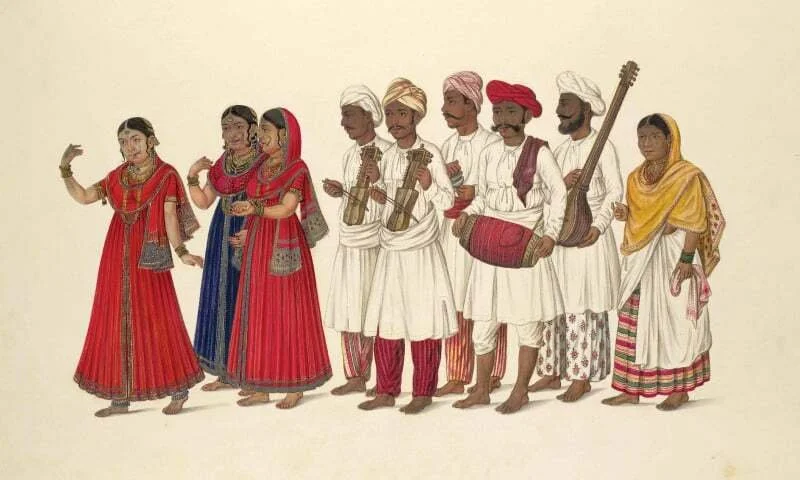

Nautch or Dancing Girls’, Mazhar Ali Khan, c. 1842. (British Library).

These women were financial revolutionaries. Contrary to societal expectations of the time, tawaifs were:

• The highest individual taxpayers in their cities

• Property owners of houses, orchards, and commercial establishments

• Independent entrepreneurs who controlled their own financial destinies

• Masters of strategic wealth accumulation

Their financial acumen was so sophisticated that they maintained multiple income streams, invested strategically, and planned for early retirement—all while navigating a deeply patriarchal society.

NOTABLE TAWAIFS

GAUHAR JAAN(26 June 1873 – 17 January 1930)

A spiritual descendant of the tawaif tradition, Gauhar Jaan represented the evolving world of performance and glamour.Her life was marked by her extraordinary talent and flamboyant lifestyle, which set her apart from other tawaifs of her time. Known for her lavish parties, one of the most famous stories involves her spending ₹20,000 on a celebration when her cat gave birth to kittens.Her glamorous photographs adorned matchbox covers globally Her boldness extended beyond her art; she defied British colonial rules by riding a four-horse carriage through the streets of Calcutta. When fined ₹1,000 for this act, she simply paid the penalty and continued her evening rides.

Her audacious spirit and extravagant lifestyle made her a cultural icon. Despite societal norms, Gauhar lived unapologetically, earning significant wealth through her groundbreaking recordings—over 600 songs in more than ten languages between 1902 and 1920. She was known as “India’s first recording superstar” and helped popularize Hindustani classical music in its condensed form for gramophone records.Frederick William Gaisberg, an engineer with Gramophone and Typewriter Ltd, recalled her legendary style noting that she always arrived in the finest outfits and never repeated her jewellery

AMRAPALI(c. 500 BCE)

Still from the movie AMRAPALI

One of the most renowned nagarvadhu (royal courtesans) of ancient India, was celebrated as the “bride” of Vaishali. She was also honored with the title Vaishali Janpad Kalayani, awarded to the most beautiful and talented woman in the kingdom for seven years. As per tradition, Amrapali had the freedom to choose her lovers but was prohibited from committing to any one man.

Still from the movie AMRAPALI

Her extraordinary beauty and talent attracted admirers from far and wide, and her fame brought glory to Vaishali. The price to witness her performances was fifty Karshapanas per night, making her wealth surpass that of many kings. Her life symbolized opulence and power, yet she eventually renounced it all, embracing Buddhism and dedicating herself to serving others.

Amrapali greets Buddha", ivory carving, National Museum of New Delhi

RESISTANCE AND RESILIENCE

When British colonial authorities attempted to marginalize them, tawaifs responded with extraordinary resilience:

• They maintained two sets of financial records to outwit intrusive authorities

• Bribed officials to protect their interests

• Publicly refused to submit to unjust regulations

• Continued to assert their economic and cultural independence

These women were not just cultural performers but political actors. In June 1857, during the Indian rebellion against British rule, a courtesan was documented fighting alongside soldiers, armed with pistols—a testament to their complex and powerful role in society.

Engraving by J Chapman of a man and two women, all belonging to the Palace of Delhi. An omrah is a grandee of a Muslim court. An Omrah of State; a Dancing Girl; and a Lady of the Harem, India, 1809.

FRANCE

THE DEMIMONDE

In nineteenth-century France, a complex taxonomy of sex work existed, strictly regulated under the French system of maisons de tolérance (regulated brothels). At the lowest levels were filles en carte (registered prostitutes) who worked in licensed brothels or as streetwalkers. Above them were the lorettes (named after the Notre-Dame-de-Lorette church district where many lived), who maintained small apartments and a modest clientele.

HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC

AU SALON DE LA RUE DES MOULINS (2)

1894

Higher still were the “grandes horizontales” or “femmes galantes” who entertained wealthy bourgeois clients. At the pinnacle stood the demimondaines—courtesans of the Parisian "half-world" that existed between respectable society and common prostitution—who elevated the strategic use of luxury to unprecedented heights. These women, immortalized in works like Alexandre Dumas fils' play "Les Demimonde" and Émile Zola's novel "Nana," transformed material acquisition into a spectacular art form that both shocked and fascinated French society.

The most successful of these women, such as La Païva (Esther Lachmann), Cora Pearl, and Caroline Otero ("La Belle Otero"), amassed extraordinary collections of jewelry, art, and luxury furnishings. La Païva's legendary hôtel particulier on the Champs-Élysées—with its onyx staircase, silver bathtub, and walls adorned with precious stones—stands as perhaps the ultimate monument to courtesan collecting. These women understood that spectacular possessions were not merely symbols of wealth but instruments of social transformation.

MATERIAL CULTURE OF THE DEMIMONDE

The collecting practices of these women also significantly influenced Parisian fashion and interior design. Demimondaines were often early adopters of new styles, unbound by the conservative tastes that constrained "respectable" women. Their patronage of designers like Charles Worth and furniture makers like François Linke helped shape the aesthetic sensibilities of the Second Empire and Belle Époque periods. Through strategic acquisition and display, these women transformed material goods into cultural capital, achieving remarkable social mobility in a rigidly stratified society.

LA PAÏVA,

COUNTESS HENCKEL VON DONNERSMARCK (1819-1884)

Few figures embodied opulence quite like La Païva, a legendary courtesan whose mansion on the Champs-Elysées was a testament to extravagance beyond imagination—more than a home, it was a palace of desire, a monument to the excess of the Second Empire, where luxury knew no bounds and personal comfort was an art form elevated to its most extreme expression.

Widely regarded as the most celebrated courtesan of 19th-century France, her remarkable ascent from humble beginnings in Russia to the pinnacle of European aristocracy captivated society. When she met the 22-year-old Prussian industrialist and mining magnate—one of Europe's wealthiest men—he was instantly entranced by her alluring charm, brilliant intellect, and exceptional business acumen.

In 1855, shortly after beginning their relationship, La Païva acquired a prestigious plot on the Champs Elysées. The resulting Hôtel La Païva became one of the avenue's most opulent mansions, featuring a magnificent central staircase crafted from Algerian yellow onyx that complemented her yellow Donnersmarck diamonds.The staircase was so remarkable that it inspired a literary adaptation by playwright François Ponsard. Her lavish soirées and literary gatherings quickly became the talk of Paris, drawing luminaries such as Gustave Flaubert, Émile Zola, artist Eugène Delacroix, and even the Emperor himself.

The pinnacle of La Païva’s decadence was her bathing ritual, which transformed personal hygiene into a performance of unimaginable luxury. Her centerpiece was a monumental bathtub sculpted by Donnadieu from a single block of yellow onyx, weighing an incredible 900 kilograms and measuring 1.85 meters in length.with champagne flowing from the tap.

This wasn’t just any ordinary onyx. The stone came from a Roman quarry rediscovered near Oran, Algeria, in 1849. So rare and prestigious was this material that it was used only in the most elite buildings during the Napoleon III era. At the Universal Exhibition of 1867, Donnadieu received a distinguished honor for his “onyx marbles designed with the elegance which is the supreme attribute of Parisian workers.”

But the true marvel was the bathtub’s functionality. La Païva didn’t simply bathe—she performed rituals of liquid indulgence. Her bathing options were legendary:

• Milk baths for skin preservation

• Lime-blossom infusions for fragrance

• Champagne baths for pure, unbridled decadence

Another silver bathtub in her collection was even more extraordinary, equipped with three taps—one presumably for water, but the others dedicated to milk and champagne.

As if her architectural and bathing extravagances weren’t enough, La Païva possessed jewels that would become the stuff of legend. Unlike most 19th-century French courtesans whose jewelry purchases remain poorly documented (as they were typically ordered and paid for by their gentlemen companions), La Païva's transactions are exceptionally well-recorded. Her passion for fine jewelry led her to frequently purchase stones by the dozen rather than individually

THE EXTRAORDINARY DONNERSMARCK DIAMONDS

The Donnersmarck Diamonds formed a cornerstone of the illustrious collection belonging to La Païva. La Païva's passion for exquisite jewels was legendary, having amassed an impressive collection even before her marriage. Her husband ensured her collection remained unrivaled.

The magnificent Donnersmarck Diamonds consist of two extraordinary stones:

- A cushion-shaped diamond weighing 102.54 carats

- A pear-shaped diamond weighing 82.47 carats

The diamonds remained within the Donnersmarck family for over a century until their appearance at Sotheby's auction in 2007.These exquisite gems were offered as a single lot with an estimate of $9,000,000–14,000,000 (CHF 8,810,000–13,700,000).

THE BOUCHERON CONNECTION

During her final Paris residence between 1878 and 1883, La Païva visited Boucheron's Palais Royal boutique over 30 times. One particularly remarkable visit on October 27, 1882, recorded her purchasing a single pearl for 60,000 francs, several emeralds totaling 203 carats, multiple rubies, a 43-carat sapphire, and 24 pearls—spending an astounding 157,957 gold francs in one day. The following day, she returned to commission settings for these treasures.

Between 1878 and 1883, Countess Henckel von Donnersmarck spent approximately 100,000 francs annually at Boucheron. One of her most significant acquisitions was a diamond collerette of triangular design, ordered on June 19, 1878, featuring 207 of her own diamonds complemented by Boucheron's addition of 220 brilliants and 526 rose-cut diamonds. This piece was later transformed into a tiara for Princess Katharina, Count Henckel von Donnersmarck's second wife.

A fascinating Boucheron archive entry from December 19, 1882, documents La Païva bringing 22 colored jewelry pieces, primarily emeralds, rubies, sapphires, and turquoise, to commission specialized steel-cornered boxes. This entry confirms her ownership of the emerald necklace and brooch featured in this sale, which her husband later bestowed upon his second wife, Countess Katharina, after their marriage in 1887.

La Païva's final Boucheron visit occurred on March 14, 1883, when she ordered two special jewelry boxes with steel corners and Fichet locks for her pearl and diamond pieces, along with three scarlet fabric covers for these boxes and a third containing her colored jewels. Her last purchase was a large leather travel bag to safely transport all three boxes.

One can easily envision the still-beautiful Countess departing her Champs Elysées mansion (which still stands at number 25) for her final journey to Prussia, followed by her chambermaid carrying the famous Boucheron leather bag containing three morocco boxes filled with an extraordinary treasure of pearls, diamonds, rubies, emeralds, sapphires, and turquoise.

Hidden for decades, some of the most significant pieces from this collection are now presented for the first time in 125 years—not merely as exceptional gemstones but as stunning mementos of a vanished era and the remarkable woman who was both courtesan and countess during the Second Empire.

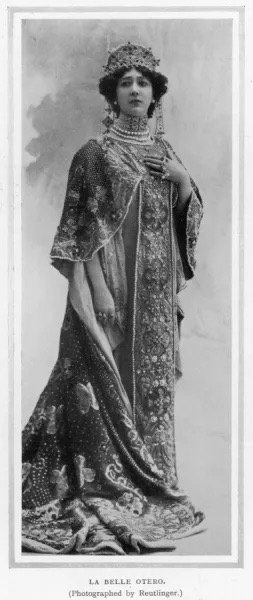

LA BELLE OTERO:

Caroline Otero, known as La Belle Otero, was a legendary Spanish dancer and courtesan who epitomized the extravagance of the Belle Époque. Her most remarkable possession was not just her beauty or talent, but her breathtaking collection of jewels that became the stuff of Parisian legend.

In 1903, Cartier created a stunning bolero for Otero that was nothing short of a wearable work of art. This sleeveless jacket was a marvel of jewelry craftsmanship, constructed using a technique called “Resille” - a delicate, openwork lattice structure that literally translates to “hair net.” The bolero was so extraordinary that it was displayed for six months in the window of the Paris jeweler Hamelin, drawing crowds and creating a sensation featuring an intricate design reminiscent of the infamous necklace at the center of the “Queen’s Necklace” scandal associated with Marie Antoinette. Its design included long stripes with delicate tassels and bows, creating a mesmerizing effect of movement and light.

Otero’s jewelry collection was legendary, even by the standards of the most opulent courtesans of her time. At a single performance at the Paris Opera, she would appear dripping obscenely in diamonds and precious stones:

• A magnificent necklace that once belonged to Empress Eugenie

• Another necklace from the Austrian Empress (later purchased by Cartier for $200,000)

• A spectacular pearl necklace from Leonide Leblanc, consisting of 212 pearls weighing 3,300 grains and valued at $36,000

• A sparkling diamond tiara crowning her hair

• Two massive 50-carat diamonds as ear studs

SARAH BERNHARDT.

Portrait of Sarah Bernhardt

Georges Clairin

Paris, 1843 - Belle-Île-en-Mer, 1919

Far more than the most celebrated actress of her time—Bernhardt was a true Renaissance woman whose artistic vision extended far beyond the stage, encompassing jewelry design, sculpture, and a revolutionary approach to performance and personal style.

When she embarked on her first United States tour in 1880, she did so with the theatrical equivalent of a royal procession. Traveling with approximately 40 trunks—some crafted by the legendary Louis Vuitton—and chartering her own Pullman train, she was a spectacle unto herself. Her costumes were so extravagant that U.S. customs officials suspected she was importing luxury goods for sale, mistaking her theatrical wardrobe for commercial merchandise.

Sarah Bernhardt was the first theatrical star to introduce the decadent glamour of the Parisian stage to America. She is credited for launching the craze for art nouveau jewelry in the 1890s, when René Lalique and Alphonso Mucha began designing ornaments for her performances.

Her relationship with René Lalique epitomized her artistic vision. When Lalique was just beginning his career, Bernhardt recognized his potential and commissioned him to create jewelry both for her stage performances and personal use. Their collaboration was transformative:

• For her role in La Princesse Lointaine, Lalique created a masterpiece: a pendant in gold, enamel, diamonds, and amethyst

• He designed an extraordinary closed crown covered with pearls and fancy stones

Another remarkable collaboration was with Alphonse Mucha, who designed a serpent bracelet that became a legendary piece of Art Nouveau jewelry. Created in partnership with jeweler Georges Fouquet in 1899, this extraordinary piece was described by art historian Dr. Jeremy Howard as “one of the most striking examples of [Mucha’s] work.”

The bracelet was a marvel of design:

• A snake coiled around the wrist

• Its tail extending up the arm

• A winged head set with a mosaic of enamel, opals, rubies, and diamonds

• Connected by delicate chains to a matching finger ring

• Ingeniously hinged to allow natural hand movement

Yet for all her theatrical brilliance, Bernhardt’s artistic soul found its deepest expression in sculpture. Her marble and bronze works were so remarkable that they were celebrated at the Universal Exhibition of 1900 and continue to be displayed in the prestigious Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

Atelier de sculpture de Sarah Bernhardt

Bourgoin, Marie Désiré , Dessinateur

En 1877

19e siècle: Atelier de sculpture de Sarah Bernhardt | Paris Musées

ÉMILIE VALTESSE DE LA BIGNE:

Her most legendary acquisition was a bed that would become the stuff of literary legend. Commissioned from the renowned designer Édouard Lièvre, this was no ordinary piece of furniture, but a monumental work of art that would later inspire Émile Zola’s iconic description of Nana’s bed in his groundbreaking novel.The price was staggering: 50,000 francs—equivalent to one-third the cost of an entire mansion.

Édouard Lièvre (1828-1886), Lit de parade de Valtesse de la Bigne, Paris, vers 1875 source: Édouard Lièvre (1828-1886), Lit de parade de Valtesse de la Bigne, Paris, vers 1875

Valtesse’s artistic vision extended far beyond her bedroom. She was a true patron of the arts:

• She commissioned paintings from Édouard Detaille, one of the most celebrated military painters of the time

• Purchased a sumptuous house in Ville-d’Avray, transforming it into a personal gallery and sanctuary

• Acquired a private carriage to traverse Paris, ensuring her movements were as stylish as her living spaces

HONOURABLE MENTION: MAÎTRESSE EN TITRE

French courtesans and French royal mistresses differed significantly in their roles, status, and influence but should be included in the converation of wealth and sexual capital because they share critical intersections in their negotiation of social capital, beauty, and economic power. Including royal mistresses in this conversation enriches our understanding of how women strategically navigated patriarchal systems of power and economic exchange.

Painting of Diane de Poitier, who remained for more than twenty years the favorite of Henry II, King of France.

by François Clouet

Date de création : 1571

The book “The creation of the French royal mistress” by Tracy & Christine Adams reveals a sophisticated political landscape where gender roles were far more nuanced than traditional historical narratives suggests. It chronicles how in the fifteenth century, various societal and cultural structures converged to create a formalized space for the royal mistress at court.

One foundational idea was the paradoxical perception of gender: while women were legally subordinate to men, they were considered equally competent politically. This led to queens being viewed as ideal regents and mistresses as reliable counterparts to royal favorites. Additionally, the Renaissance introduced a theatrical understanding of space, which linked political cunning with the role of the royal mistress.

However, this position required activation by an intelligent, charismatic woman aligned with a king receptive to female advisors.The French royal mistress was not merely a sexual companion but a carefully crafted political and social institution, an extraordinary parallel to the tawaif culture of India. Emerging during the Renaissance and reaching its zenith in the 17th and 18th centuries, the royal mistress represented a complex nexus of power, wealth, and cultural sophistication that transformed the very fabric of the French court.

Unlike casual affairs, the position of royal mistress was almost an official role—a structured position with its own intricate protocols, social expectations, and economic rewards. Much like the tawaifs who carefully cultivated their patrons, French royal mistresses were masters of strategic seduction, political negotiation, and economic manipulation.

WEALTH BEYOND IMAGINATION

The financial landscape of a royal mistress was staggering:

• Châteaux gifted as personal properties

• Annual incomes that rivaled and often exceeded those of high-ranking nobility

• Jewels, art collections, and extensive wardrobes that represented massive personal wealth

• Political appointments for family members

• Direct influence over royal policy and court politics

A royal mistress’s wealth was not just about gifts but about systematic wealth accumulation. Like the tawaifs who invested in properties and businesses, these women were Cultural Arbiters and Patrons of the Arts who commissioned elaborate artworks, Set fashion trends that rippled through European high society and established salons that became intellectual and cultural hubs

NOTABLE EXAMPLES

AGNÈS SOREL(1422–1450)

Agnès Sorel is widely recognized as the first official French royal mistress. Her relationship with King Charles VII, beginning in 1444, elevated her to a quasi-official status at court, unprecedented for mistresses of earlier monarchs. She wielded significant influence, advising Charles and inspiring him to take decisive actions, such as restoring order in his kingdom and rejoining the conflict against England.

Sorel’s status was marked by extravagant gifts, including estates, castles, rare jewelry, and ceremonial crockery. She was one of the first commoners to wear diamonds, a privilege previously reserved for elites. Her wardrobe reflected her elevated rank, featuring luxurious fabrics like damask and velvet. Georges Chastellain noted that her possessions were fit for royalty, including “the best rings and jewels” and “the finest tapestries”.

Her fashion choices were groundbreaking; she popularized bold styles such as square-cut necklines and corsages. Her influence extended beyond court politics to art and culture; she inspired Jean Fouquet’s Virgin and Child Surrounded by Angels, which immortalized her beauty.

Sorel died suddenly at age 28 in 1450, possibly due to poisoning. Her legacy reshaped the role of royal mistresses in France, establishing them as influential figures within the monarchy

MADAME DE POMPADOUR (1721-1764)

His wife, Queen Marie, is said to have remarked, "If there must be a mistress, better her than any other." At court, Pompadour was careful to stay on the queen's good side, and show her respect.

• Madame de Pompadour was a pivotal figure in 18th-century France, celebrated for her political influence, artistic patronage, and cultural contributions during King Louis XV’s reign. Born Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, she rose from bourgeois origins to become the king’s official mistress in 1745 and held power as his confidante until her death.

Pompadour was a remarkable patron of the arts, commissioning works from celebrated artists like François Boucher and Jean-Marc Nattier. She actively engaged in artistic creation herself, carving gemstones and producing etchings. Her artistic talents were showcased in her ability to transform designs into new forms, reflecting her creativity and technical skill.

PORCELAIN COLLECTION

Her porcelain collection was equally impressive, featuring nearly 300 pieces of Far Eastern porcelain, primarily Chinese. These included celadon, monochrome lapis lazuli objects, and rare blancs de Chine, many adorned with gilt bronze mounts in the Rocaille style. Pompadour acquired these through prominent Parisian dealers like Lazare Duvaux and Edme-François Gersaint. Her purchases began in 1750 and continued until 1757, with a notable decrease after that period. The collection was highly sought after by dealers like Simon-Philipe Poirier after her death.

SÉVRES

SÈVRES MANUFACTORY.

Pompadour played a crucial role in the development of the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory. In 1756, she initiated the relocation of the factory from Vincennes to Sèvres, near her Château de Bellevue. This strategic move helped establish Sèvres as a premier center for porcelain production, renowned for its exquisite craftsmanship and innovative designs. Her patronage of Sèvres not only supported French artisans but also promoted French identity and Rococo artistry globally.

Lorgnette belonging to Madame de Pompadour (Musee des Arts decoratifs), 18th century.

MADAME DU BARRY (1743-1793)

Madame du Barry, born Jeanne Bécu in 1743, rose from humble beginnings to become the last official mistress of King Louis XV. Her life was marked by scandal, opulence, and a deep appreciation for the arts, leaving behind a legacy that intertwined her personal story with the cultural achievements of 18th-century France. In 1768, Jeanne was introduced to Louis XV by his valet de chambre, Le Bel, who also oversaw the king’s secretive Parc-aux-Cerfs. Their romance began that summer, with Jeanne captivating the nearly sixty-year-old monarch through her charm, vivacity, and skill in the “arts of love.”

PATRONAGE OF ART AND DECORATIVE ARTS

Madame du Barry’s love for beauty extended beyond her personal appearance; she was an ardent supporter of the arts and decorative crafts. Her patronage played a significant role in shaping the Neoclassical style that defined late 18th-century French culture.

PAINTING

Du Barry commissioned works from celebrated painters such as Jean-Honoré Fragonard, François-Hubert Drouais, and Joseph-Marie Vien. Fragonard famously created The Progress of Love, a series of romantic paintings intended for her music pavilion at Louveciennes. These works featured lush landscapes and intimate scenes that reflected Du Barry’s taste for elegance and sensuality. Although Fragonard’s paintings were ultimately replaced by more restrained works from Vien, they remain iconic examples of Rococo art.

The Progress of Love,Jean-Honoré Fragonard

FURNITURE AND DECORATIVE ARTS

Madame du Barry surrounded herself with exquisite furniture crafted by some of the finest artisans of her time. She worked closely with Louis Delanois, a master joiner specializing in chairs; Jean-François Leleu, a cabinetmaker known for his refined craftsmanship; Martin Carlin; and Pierre Gouthière, who created intricate gilt-bronze objects adorned with Neoclassical motifs like laurel wreaths and myrtle leaves. Gouthière’s creations included firedogs, doorknobs, and other decorative pieces for Du Barry’s residences.

Her Louveciennes estate became a showcase for these artistic achievements. Designed by architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, it featured the Pavillon de Musique—a Greek temple-inspired structure overlooking the Seine. This pavilion housed many of Du Barry’s commissioned artworks and served as a retreat where she could enjoy music and entertain guests.

JEWELRY

In 1772, Louis XV commissioned jewelers Charles-Auguste Boehmer and Paul Bassange to create an elaborate diamond necklace for Madame du Barry. The piece was so ornate that it took several years to complete. However, by the time it was finished, Louis XV had died of smallpox in 1774, and Du Barry had been removed from court under orders from Louis XVI.

The necklace inspired The Affair of the Diamond Necklace.

AFFAIRE DU COLLIER DE LA REINE

The Affair of the Diamond Necklace (Affaire du collier de la reine) was a scandal from 1784 to 1785 at the court of King Louis XVI of France that deeply tarnished Queen Marie Antoinette’s reputation. Originally, the extravagant necklace was commissioned by Louis XV for his mistress, Madame du Barry, but remained unsold after his death, leaving jewelers Boehmer and Bassenge in financial distress. Attempts to sell it to Queen Marie Antoinette failed as she declined the purchase.

The scandal unfolded when Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Rémy (Jeanne de la Motte), an adventuress, orchestrated a scheme involving Cardinal de Rohan. Jeanne convinced Rohan that the queen secretly desired the necklace but needed him to act as an intermediary. Through forged letters and a staged meeting with a prostitute impersonating the queen, Jeanne manipulated Rohan into purchasing the necklace on her behalf. The jewels were then dismantled and sold on black markets.

Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Rémy (Jeanne de la Motte)

When payment issues arose, the jewelers appealed directly to Queen Marie Antoinette, exposing the fraud. Although she was uninvolved, public perception linked her to the scandal, exacerbating her unpopularity amidst growing discontent with royal extravagance. The affair significantly discredited the monarchy and fueled revolutionary sentiment, marking a pivotal moment leading up to the French Revolution. Marie Antoinette’s reputation never recovered, and she became a symbol of perceived royal excess and corruption

Queen Marie Antoinette

Following Louis XV’s death, Madame du Barry was banished from Versailles by Marie Antoinette’s faction but continued to live comfortably at Louveciennes until her execution. She maintained friendships with intellectuals like Voltaire until his death in 1778 and remained devoted to her art collection.

STRUCTURAL SIMILARITIES WITH TAWAIF CULTURE

The parallels between French royal mistresses and Indian tawaifs are profound:

Economic Independence: Both groups maintained significant financial autonomy in deeply patriarchal societies

Cultural Sophistication: Mastery of arts, intellectual discourse, and social graces

Strategic Relationship Management: Carefully negotiated relationships with powerful men

Social Mobility: Ability to transcend traditional social boundaries

Artistic Patronage: Crucial supporters of cultural production

Both French royal mistresses and tawaifs understood that luxury was not just about possession, but performance.

Interestingly, both groups faced similar historical trajectories:

• Initial periods of significant social and cultural influence

• Subsequent marginalization and moral condemnation

• Deliberate erasure of their complex cultural contributions

• Reduction to simplistic sexual narratives

OBJET AS AGENCY

Across these diverse cultural contexts, courtesans' relationships with luxury objects transcended simple ownership. Their carefully curated possessions functioned as tools for self-fashioning, markers of cultural capital, and instruments of economic advancement. Through strategic acquisition and display of precious items, these women—often working within significant societal constraints—established spaces of cultural authority and personal agency.

The material culture of courtesanship reveals how these remarkable women leveraged luxury objects to navigate complex social landscapes, forge economic independence, and influence cultural taste. While the artistic practices of non-white courtesans have often vanished without trace, their legacy lives on in the material record of their possessions and the spaces they created—testaments to their ingenuity, cultural sophistication, and strategic brilliance in merging art, commerce, and intimacy.